(By Gordon T Long) It was always blatantly clear that an EU monetary union would inevitably require a political union to centralize decisions about tax and public spending. Without this occurring it was a misconceived and terrible blunder (that some of us argued it was when it was initially constructed) but it is turning out to be even worse than we originally perceived because of its underpinning Euro currency.

We are now witnessing that the EU experiment has become so damaging and divisive that public opinion will now never tolerate a political union. So not only was the cart put before the horse, but the horse will not now contemplate even following the cart at a distance!

One of the reasons is that it has made countries, like Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece, poorer while others got richer. Forcing many countries to have the same interest rates and exchange rate was foreseeable always going to be a problem, as it would lead to some countries having booms followed by big busts, as has happened in Ireland, Portugal and Spain.

It has lead to per capita income of Italians for example being lower now than in 2000, which is why they are – not surprisingly – getting increasingly restive, while in the meantime, the German economy has kept on growing, and the average German is about 20 per cent better off over the same period. The euro is a cheaper currency than the Germany Mark would have been if it still had the deutschmark, while it is more expensive than Italy would have if it still used the Lira. Germans therefore keep exporting easily and running up a surplus, while the Italians struggle and go deeper in to debt.

It has lead to per capita income of Italians for example being lower now than in 2000, which is why they are – not surprisingly – getting increasingly restive, while in the meantime, the German economy has kept on growing, and the average German is about 20 per cent better off over the same period. The euro is a cheaper currency than the Germany Mark would have been if it still had the deutschmark, while it is more expensive than Italy would have if it still used the Lira. Germans therefore keep exporting easily and running up a surplus, while the Italians struggle and go deeper in to debt.

Furthermore, the freedom of movement of capital in Europe probably makes this worse – why would you put your euros in an Italian bank when you can invest them in Germany? Membership of the euro has thus put the Italians (and what we once politically incorrectly referred to as the PIGS) on a permanent path to being poorer.

Simply stated, the euro zone doesn’t have the fiscal or banking unions it needs to make monetary union work, and it’s not close to changing that. In the meantime, the euro’s continuing flaws continue to suck countries into crisis. And their politics get radicalized out of misunderstood populist frustrations.

A FAILED CURRENCY

The Atlantic pointed out the flaws the Euro was facing back in 2013 shortly after the EU Banking Crisis, which has been steadily deteriorating since as result:

1. Too Tight Money

The euro zone isn’t what economists call an “optimal currency area”. In other words, it was a bad idea. Its different members are different enough that they should have different monetary policies. But they don’t. They have the ECB setting a single policy for all 17 of them. That’s a particular problem for southern Europe now, because their wages are uncompetitively high relative to northern European ones, and the ECB isn’t helping them out.

There are two ways to fix this intra-euro competitiveness gap. Either northern European wages rise faster than normal while southern wages stay flat, or northern European wages grow normally while southern European wages fall. It’s the difference between a bit more inflation or not — in other words, between looser ECB policy or the status quo. Now, it might not sound like it really matters which option they choose, but it very much does. Falling wages make it harder to pay back debts that don’t fall, setting off a vicious circle into economic oblivion.

2. Too Tight Budgets

Austerity has been a complete disaster. It’s actually increased debt burdens across southern Europe, because it’s reduced growth more than it’s reduced borrowing costs. And now northern Europe is getting in on the act. France (which is really somewhere in between “southern” and “northern”) just missed its deficit target, and is set to slash more; the Netherlands has put through contentious tax hikes and spending cuts, even as its economy has shrunk; and even Germany is contemplating new budget-saving measures. In other words, the euro has become an austerity suicide pact.

3. Too Little Trade

Excluding Germany, just over half of all euro trade is with each other. But with bad policy pushing southern Europe into depression and northern Europe towards recession, euro zone countries can’t afford to buy as much stuff from each other. That adds a degree of difficulty to recovery for southern European countries that need to export their way out of trouble. As you can see in the chart to the right from Eurostat, intra-euro zone trade has stagnated the past few years (and headed lower since) after rebounding from its post-crash depths. The euro zone’s weak links are dragging the rest down — but only because the rest refuse (or can’t) to pull the weak ones up.

4. Too Much Financial Interconnection

Other country’s problems can quickly become your own if your banks own their bonds. Especially if your banks are bigger than your economy. That’s the lesson Cyprus learned the very hard way after its banks loaded up on Greek debt in 2010, only to get wiped out a year later. The Financial Times has a great infographic (that you should play around with) on which country’s banks are exposed to which other country’s debt across the euro zone. As you can see below, any kind of Italian restructuring would be tremendously bad for French banks.

THE ERUPTION HAS BEEN BUILDING

The mood in the EU has been steadily changing since the initial “Enactment Era” as we then entered the “Expansion Era”, then the “Bailout Era” and now appears to be inevitably heading towards the “Depression Era”!

THE ERUPTION OF EXPLODING POPULISM

This mood shift which I recently explored in a video with Charles Hugh Smith illustrated that Political Polarization, Lack of Cooperation, Rebellion against Political Correctness are all presently manifesting themselves into a rejection of the status quo, “the system” and those trusted with its maintenance.

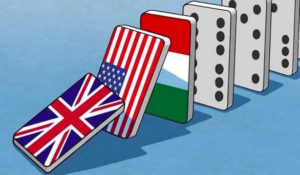

The rapid emergence of new anti-establishment populist parties skeptical of the European integration are all strong indicators of the failure of the Euro Experiment which we cautioned about years ago.

We foresee a steady sequential set of highly charged political events throughout Europe coming in 2017 which portends of mounting political instability and social unrest.

Souring social mood, loss of purchasing power, stagnating wages, rising inequality, devaluing currencies, rising debt, political polarization and elite disunity are all manifestations of a phase Charles Smith and I labeled as the “Dis-Integrative Winter” in our analysis of long wave cycles: CYCLES – ANTI-GLOBALIZATION & THE END OF THE DEBT SUPER CYCLE.

There is a “Dis-integrative Winter” stage to all of our cycles.

AN INCREASE IN NATIONALISM & A REVERSAL IN THE GLOBALIZATION TREND

The EU Experiment is also facing something completely unexpected but tremendously important. A shift globally away from Globalization and towards Nationalism – exactly the wrong development for the experiment to move in the direction it requires to have any possibility of success.

The June 2008 issue of Progress in Socionomics reported:

Scientist predicts a reversal of the trend toward globalization. Dr. John L. Casti’s presentation at the Cycles and Patterns in Business and Finance Conference depicted and expanded upon Elliott Wave International’s forecast of a reversal in the trend toward globalization.

THERE IS NO EXIT FROM THE EURO!

In implementing BREXIT (which like the Italian Referendum toppled the government), Prime Minister Theresa May is going to have substantial problems with exiting the EU but at least it always maintained the Sterling!

Leaving the euro, however, is a far more difficult problem than leaving the EU. As everyone now knows, Article 50 provides for leaving the latter. It may be a vague and inadequate rule, on which our Supreme Court is now deliberating at length, but it is nevertheless a rule that provides for getting out.

The eurozone has no such rule. This is a burning building you are never meant to leave. What is more, you are barricaded in. If you contemplate leaving, you have to face not having any notes and coins of your own; the need to default on debts that will be even bigger when your new currency goes down in value; and the collapse of your banks because being in the eurozone means they were able to borrow money they should never have been lent.

Tens of millions of people in southern Europe will increasingly find that they cannot tolerate staying in the euro, but nor can they leave it without great cost.

Their anger and resentment will only intensify.

GOLD STANDARD VERSUS A FIAT EURO

The Atlantic postulated in 2013:

The euro is the gold standard minus the shiny rocks. Both force countries to give up their ability to fight recessions in return for fixed exchange rates and open capital flows. But giving up the ability to fight recessions just makes it easier for recessions to turn into depressions. And that puts all of the pressure on wages to adjust down when a shock hits — the most painful and destructive way of doing things.

But the gold standard had an even bigger design flaw than creating depressions. That was perpetuating depressions. Under the rules of the game, countries short on gold were supposed to raise interest rates, which would push down wages, and push up exports. More exports would mean more gold, and then lower interest rates. But there was an asymmetry. Countries needed gold to create money, but countries didn’t need to create money if they had gold. During the Great Depression, the U.S. and France sucked up most of the world’s gold, but didn’t turn it into money out of fear of nonexistent inflation. Countries that needed gold needed to push down wages even more to make their exports competitive — not that there were any booming markets for them to export to, due to the self-inflicted economics wounds of the U.S. and France. Instead, the depression just fed on itself.

The euro suffers from a similar asymmetry. Debtor-euro countries are to cut wages and deficits, but creditor-euro countries aren’t forced to increase wages and deficits. Perversely, the opposite. In other words, northern Europe isn’t doing enough to offset the demand destruction in southern Europe. And it’s sinking them all. Even worse, this slow-motion collapse is turning loans that would have otherwise been good into losses — losses that force bailouts and faster collapses. But, to be clear, this isn’t only a problem for the periphery. As the U.S. and France found out in the 1930s, it’s generally not a good idea to force your customers into bankruptcy. That just creates depression without end — until the gold (or euro) standard ends. It’s no coincidence that the countries that ditched the gold standard first recovered from the Great Depression first.

History doesn’t need to repeat, or even rhyme. Europe doesn’t have to keep crucifying itself on a cross of euros, the gold standard of the 21st-century. The euro’s northern bloc could decide to let the ECB do more. Or it could decide to start spending more. Or not. Eurocrats seem content to do just enough to keep everything from falling apart, and nothing more. It’s one part inflationphobia, and another part strategy. Indeed, it’s how they try to keep the pressure on the southern bloc to push through unpopular labor market reforms. But doing enough today eventually won’t be enough tomorrow if the southern bloc doesn’t have any hope of recovering within the euro. The politics will turn against the common currency long before that.

Things that don’t bend, though, break.