The long-promised end of quantitative easing by the Fed last fall never happened, and, strangely, no one has called the Fed on that. I cry foul because I bet my blog ( TheGreatRecession.info ) that it would become clear, once quantitative easing ended in the fall, that there has been no economic recovery. I also predicted the stock market, which has been inflated by all that easing money, would crash in the fall. While it did take a big plunge at the mere thought that QE was ending, it also quickly recovered. Now, when I look back at the Federal Reserve’s own data, I see why.

As soon as the stock market plummeted in October 2014, one of the Fed’s board members stated there might be a new fourth round of quantitative easing (QE4). Immediately, the stock market bounded back upward in euphoric hope. What I didn’t see back then was that the Fed moved immediately into QE4 without saying a further word.

And nobody seems to know it happened.

What does it mean to end quantitative easing?

In other words, the Fed buys bonds and other assets from its member banks by creating new money credits in their reserve accounts. Wikipedia goes on to explain the difference between quantitative easing and normal monetary expansion:

Expansionary monetary policy to stimulate the economy typically involves the central bank buying short-term government bonds in order to lower short-term market interest rates. However, when short-term interest rates reach or approach zero, this method can no longer work. In such circumstances monetary authorities may then use quantitative easing to further stimulate the economy by buying assets of longer maturity than short-term government bonds, thereby lowering longer-term interest rates.

So, “to end quantitative easing” would mean that the Fed stopped buying long-term assets, returned to shorter term assets or stopped inflating the nation’s money supply.

The Fed didn’t stop either. So, let’s look at what the Fed actually did, using its own charts and graphs.

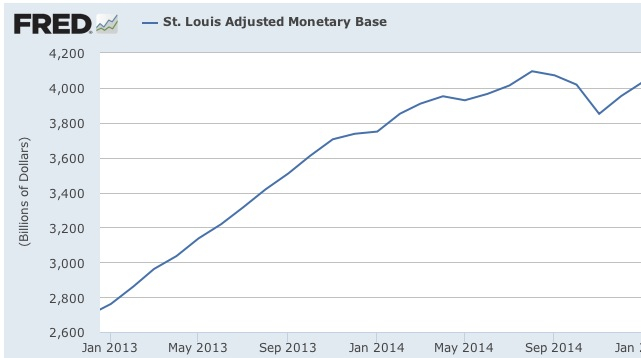

In fact, the Fed actually increased its expansion of money supply from October through the end of December. What you see above is that the annualized rate of change for the last three months of 2014 is greater than the annualized rate for the last six months of 2014. That is, in fact, a fairly sharp increase.

Let’s look at the same thing via a graph put out by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, one of the Fed’s member banks:

What you see is that the nation’s money supply plummeted in fall as the stock market plunged and then rebounded as the market rebounded. Why did both the market and the money supply rebound. Further investigation shows there is more to it than just the recovery of stock values.

One would expect that, if the Fed was going to stop QE, it would stop adding to its own balance sheet and stop creating new credits in its member bank accounts. When the Fed adds to its balance sheet in order to expand money supply under quantitative easing, it creates money out of thin air by creating deposits in the accounts at its twelve Federal Reserve Banks around the nation. This gives the banks more ability to give loans, and those loans are how the monetary base expands.

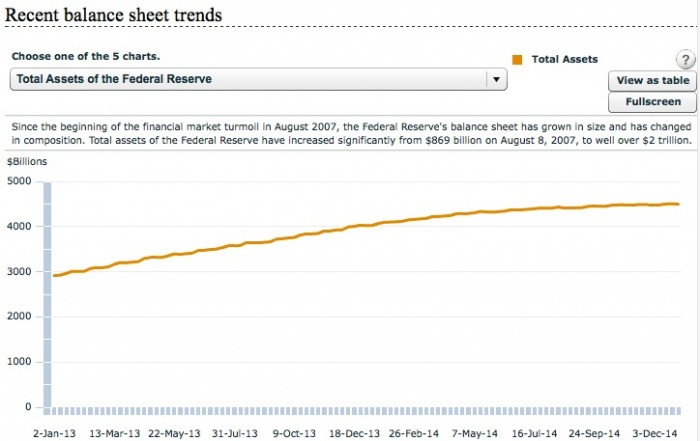

Now let’s look at whether the expansion of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet, as a key element of QE3, really ended in the fall as reported or not. Here’s the Fed’s own graph of its balance sheet:

Apparently not. You can see that the rate of expansion in the Federal Reserve’s total assets tapered as the Fed promised would happen back in 2013, but the expansion never ended. Because the graph is in trillions of dollars, the expansion rate appears gradual, but the continued increase in the fall of 2014 amounts to an additional $20 billion from October 31 to the end of December 2014.

Prior to the start of all three rounds of QE, the Fed had $900 billion in total assets on its balance sheet. At the “end” of all three rounds in 2014, it had $4.5 trillion in assets. One would also think, if they were going to end quantitative easing, they would actually start to deflate their balance sheet. In fact, they continued right on increasing it through the end of the year.

Why the end of QE3 was not the end of quantitative easing

The Fed started sucking up all that swill by crediting deposits (of money created out of thin air) in the reserve accounts of many of the nation’s banks in exchange for their bad mortgage-backed securities. The Fed sopped up the junk to bail out the banks, giving them billions in new money in exchange for their bad assets.

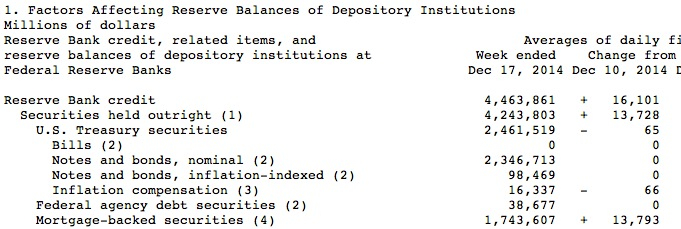

Now let’s look at a breakdown of the Fed’s assets last fall in order to see what the components were that continued its balance-sheet expansion. You can see in the table below that the Fed continued to expand U.S. money supply by returning to its practice of slopping like a hog on these bad bank securities.

The devil is in the details. In this one week, the Fed decreased its holdings in U.S. securities, but only by only $65 million. It had been adding to them at a rate of $20 billion a week at the peak of QE3 and then at a slower rate of $20 billion a month near the end of QE3. So, a drop to $65 million rolls back the Fed’s buying of U.S. treasuries. However, its holdings in mortgage-backed securities rose by over $13 billion in just one week!

If you look at other Fed charts from October 31 (when QE supposedly ended) to the end of December, 2014, you see that the Fed continued to increase its assets through purchases credited to reserve bank accounts, which adds money into the supply. Over the course of those two months, it increased its holdings of mortgage-backed securities by $26 billion. It also dropped about $7 billion in other assets for a net increase of $20 billion to the funds in reserve bank credits.

That means that, after the “end of QE3,” the Fed continued expanding its assets by $10 billion a month. That continues to grow the Fed’s balance sheet and the nation’s money supply much faster than it grew in the years of inflation prior to the Great Recession. The main change at the end of October was simply that the Fed shifted its focus away from the treasury notes bought under QE3 back to the mortgage-back securities it had purchased in earlier rounds of QE. So what! All that means is QE4 looks like the earlier rounds but on a smaller scale. In reality, the Fed just shifted to QE light (or QE4).

The Fed saw the stock market plunge simply out of fear during October because the end of quantitative easing was near, so The Fed leaked out a hint of QE4. That sent the market back up in hope.

“March data had other worrisome signs: hours worked fell, unemployment among all adult men and among African Americans rose, and the participation rate in the jobs market fell. Economist Douglas Holtz-Eakin, former head of the Congressional Budget Office, called the report ‘awful’: ‘once again the economy has failed to shift to an anticipated higher gear — an ominous development,’ he said…. Said economist Justin Wolfers of the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, ‘I don’t think it’s reasonable to be confident about much.’” (‘Former CBO Chief: ‘Awful’ Jobs Data Show US Has Yet to ‘Shift Into Higher Gear‘

“Steady hiring is supposed to fire up economic growth.

“Cheap gasoline is supposed to power consumer spending.

“Falling unemployment is supposed to boost wages.

“Low mortgage rates are supposed to spur home buying.

“America’s economic might is supposed to benefit its workers.

“Yet all those common assumptions about how an economy thrives appear to have broken down during the first three months of 2015…. During the first three months of the year, the Atlanta Federal Reserve forecasts that the economy actually came to a standstill — failing to grow at all.” (“Why Job Growth and Cheap Gas Aren’t Doing What They Should“)

There can hardly be any question that the resolute optimism of the market bulls is beginning to shake (though it won’t end until we go over the cliff because they never see until it is too late.

If QE4 started in the fall, why is the economy faltering?

Because QE4 is smaller than QE3, the result you see is a market that is no longer rising and can barely hold its top. (Moreover, I have pointed out all along that each round of QE has been less effective than the previous round because of the law of diminishing returns. QE is quite simply tired.

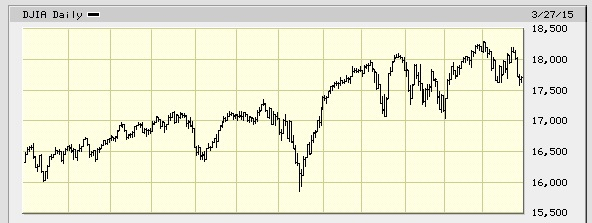

Since October, the market has plunged, tried to rise to a new high and failed a few times. It has risen marginally above its previous high just once, but only to drop right back down. The market has not been able to rally back into a bull market for half a year now. It has become an almost flat series of major spikes and equally large valleys:

The big trough in the middle of the above graph was the October crash that I predicted. While an actual crash was narrowly averted for the time, the market’s dynamics clearly changed from that point on. That is because there is just enough new money being created now to keep it alive, but not enough to make it grow. It was, as I and few others have said all along completely dependent on QE for its growth — so no sustainable recovery. The banks continue to use the new money to buy stocks; but the bull’s claims that the market will continue to rise through the year have become false for more than a quarter of a year now!

Why is the Fed silent about QE4?

To call the switch back to expanding its balance sheet through mortgage-backed securities “QE4” would be to admit that the stock market has become completely dependent on the Fed’s free money. The Fed would be admitting that it has no end-game for getting out of QE without crashing the economy. It would prove that what the Fed did with QE1-3 cannot be sustained without endless QE. So, it prefers not to call this “quantitative easing.” It’s hoping this sort of semi-QE will ween the market away from the Fed’s free money by doing QE at a lower rate and hoping this lower rate will fly under the radar.

As the market now fails to significantly break past its previous peaks, however, more and more people are starting to talk about the end of the bull market. So, as I predicted almost exactly one year ago, clarity about the world’s lack of recovery from the Great Recession began to dawn with a change that happened last fall. It’s playing out a little slower than I predicted because that rising dawn has been briefly obscured (from those who don’t want to see it anyway) by the Fed’s QE Lite.

Even if the Federal Reserve jacked QE back up to what it was before October, I don’t think you’d see much benefit because of that tiresome economic Law of Diminishing Returns. In fact, I think making QE so obvious would raise alarms that there is no end to this madness that does not result in a crash. So, watch the stories of a dying market and withering economy slowly eclipse the optimistic moonshine of the bulls.